I stare at the blank page on my laptop and tap the keyboard gently with my fingers, waiting for the words to flow. Nothing happens. I type random letters, hoping if not for a flow, then at least a trickle.

Fldkfjldsjflkdsjf

Fjdlsfjds

Still nothing. I reach for the cup of tea next to me and take a sip — it’s hot and burns my tongue. I go back to the page, willing the words to come. Usually, as soon as I sit down to write, my mind and fingers connect, and I type, fast and frantic, my fingers struggling to keep up with my thoughts. The faster I type, the faster the words appear.

But today, and yesterday, and the day before, and for most of January, my mind has been empty, drained of any creativity, the connection between mind and fingers severed.

‘What’s happening to me?’ I turn to Chris, who’s sitting at his desk next to mine, staring into a spreadsheet.

‘What do you mean?’ He doesn’t take his eyes off the columns of data on his screen.

‘I can’t write!’

‘You can.’

‘I can’t!’

He stops trying to work and looks up. ‘There’s bound to be times when it’s easy and times when it’s hard.’

‘How do you know — you’re a numbers person?’

He laughs. ‘I imagine that’s what it’s like.’

‘It’s not. I’ve always been able to bash something out.’

No matter what’s been going on in my life, I have always had words. They may not have been the best words in the best order, but they have always found their way onto the page.

‘I don’t know what’s happening,’ I say. ‘Yesterday I sat here for two hours and ten minutes and wrote a paragraph. A paragraph! What’s wrong with me?’

‘Don’t be hard on yourself,’ he says.

It’s too late. I’m already going into panic mode. ‘It’s been like this since the start of the third lockdown. Why is writing so hard? It’s never been hard before.’

‘Writer’s block?’ Chris says.

‘No! No such thing.’ I have never believed in writer’s block. I’ve always thought that if you showed up to write, the words would show up too. In twenty years of writing, they’ve been my one constant. Except now, in the middle of this second tragic wave of coronavirus, when I need to write just to cope with what’s happening, the words are failing me.

I take another drink of tea, gulping it down, not caring that it’s just below boiling point.

‘What’s that quote,’ Chris says. ‘The Hemingway one?’

‘Hemingway?’

‘You had it on a bookmark.’

‘Oh… this.’ I pull it from the bookshelf. ‘There is nothing to writing. All you do is sit down at a typewriter and bleed.’

‘That’s the one.’ He sits back in his chair and nods, as though that explains everything. ‘If Hemingway struggled, you’re bound to.’

‘Thanks.’

‘No… I meant — ’

‘I know what you meant… And at least Hemingway wrote something. All I’m doing is sitting here drinking tea, eating biscuits and getting fat.’

Chris returns to focusing on his spreadsheet. ‘Maybe you need a break. Do something else for a bit?’

He has a point. I’ve heard writers talk about the need to get out and about and fill the creative well. In normal times, I run, walk, meet friends, eat cake, go places, do things, and this is more than enough to fill the aforementioned well. But being locked in and snowed in for most of January has limited my well-filling.

I’ve only made it to the end of the road. And I didn’t find much inspiration there — just a bag of chips and an empty can of lager that someone had thrown on the pavement. Chris had complained about the littering. I’d wondered why anyone would leave a bag of chips without eating every last one.

‘The problem,’ I say, pulling my mind away from the chips and back to my dilemma, ‘is that I can’t go anywhere or do anything. And I have to write for the day job. I’ve got a 500-word article to write about irritable bowels.’

Chris smiles sympathetically.

I carry on talking. ‘And if I phoned my boss and said I was taking a couple of hours off to fill my creative well, I’m sure she’d have something to say about that.’

‘Better get back to the irritable bowels,’ he says.

My day job is a glamorous affair. When I’d imagined a writing career, I’d dreamed of writing novels that became international bestsellers. I’d write by day, and by night I’d attend literary parties and awards ceremonies in a variety of fancy frocks.

In one of my dreams, I’m on the red carpet at the Oscars because my latest novel has been made into a Hollywood blockbuster with the latest in-demand actor. (Hugh Grant always used to be my leading man but then he got too old, so I swapped him for Leonardo DiCaprio, who, being a similar age to me, is also now knocking on a bit. After I saw La La Land, Ryan Gosling became The One).

And in my dream, I never age. I’m permanently twenty-seven with long hair, flawless skin and plenty of collagen. My hair and makeup look amazing (as befitting an Oscars do) and my only concern is whether it is Oscars etiquette to eat a tub of popcorn as I would at Cineworld Wakefield. And if the answer is yes, should I accompany it with the usual bag of Minstrels?

While the dream is still very much alive in my mind, my reality is a million miles from this. I write from my home in Yorkshire, mostly at my kitchen table in various states of undress. By day, I write about irritable bowels and other health conditions, fuelled by endless cups of tea, and by night I frantically scribble stories I hope will eventually take me away from the irritable bowels.

I drink the rest of my tea, then head downstairs to make another, hoping that inspiration will strike while I stand next to the kettle (a change of scenery and all that). It’s a grey February morning. The small part of Yorkshire that I can see looks unremarkable in every way.

And suddenly it hits me: I don’t know what day it is. It feels like it’s Tuesday, but I’m not sure. The confusion is overwhelming. I feel like I’m on a ship, navigating choppy waters, so I reach for the worktop to steady myself. I think hard about the week so far, trying to differentiate one day from another. I can’t, but I know a device that can.

‘Alexa, what day is it?’

‘Today is Wednesday the third of February 2021,’ she says.

‘Alexa, are you sure it’s Wednesday?’

‘Sorry, I don’t know that.’

I ask her again. She says it’s Wednesday. I can’t have lost a day. What happened to yesterday? ‘Alexa, you’re wrong.’

‘Thanks for the feedback.’ The way she says it, in that clipped tone of hers, I can tell she doesn’t mean it.

‘Alexa, shut up.’

‘Are you arguing with a virtual assistant?’ Chris asks, walking into the kitchen.

‘Yes!’ I move to the table, pull out a chair and sink into it, putting my head in my hands. There have been many lows throughout the pandemic, but this is undoubtedly one of the lowest. ‘I thought it was Tuesday, and she says it’s Wednesday.’

‘You know you’re lacking social contact when you’re arguing with Alexa.’

‘It’s bad,’ is all I can say. ‘But it explains a lot. How can I write when I don’t even know what day it is?’

I take a deep breath, resisting the urge to go back to bed, forget about today and start over tomorrow. Instead, I grab a notepad and pen. If writing on the computer isn’t working, perhaps this will. I’m halfway through my first sentence when Olivia FaceTimes.

Seeing my lovely niece’s face pop up on screen always makes me feel better. ‘I’m so glad you’ve called,’ I tell her. ‘I was just falling out with Alexa.’

Olivia leans closer to the screen, her face serious. ‘Auntie Liz,’ she says, ‘can you help me? I have to write a description of the inside of Charlie’s chocolate factory for school.’

‘You have to describe a chocolate factory?’ I sit up straighter.

‘Just one room.’

‘Liv! That’s so exciting… Imagine being in a room full of chocolate.’

She smiles. ‘I thought you’d like that.’

‘It’s wonderful.’ In my mind, I’m already there — stepping inside, breathing in the rich smell of cocoa.

‘How should I start it?’ she says.

My mind is racing with ideas, automatically trying to form a story. ‘Imagine finding the golden ticket. How does it feel? And then you’re on your way to the factory and — ’

‘No.’ Olivia shakes her head. ‘We can’t do a story, Auntie Liz.’

‘No story.’ My heart sinks. It’s like Willy Wonka has slammed the door to his chocolate factory in my face.

‘Miss wants description,’ Olivia says.

‘Description?’

‘She’s very strict about what she wants. She’s so strict, I’m surprised she’s not written it herself.’

‘Right.’ I laugh.

‘If we were at school and wrote a story when she wanted description, she’d have ripped it up and made us start again.’

‘Would she?’ I can’t help but think Olivia is already using her imagination and creating a story.

‘Yes.’ She nods.

‘Well, if description is what she wants, that’s what she’ll get.’ I head upstairs to my desk, Chris following behind, wanting to get back to his spreadsheet pivot tables.

‘Do you think Auntie Liz is excited about this project?’ he says.

‘Just a little,’ Olivia says.

I sit down and prop the phone up against my laptop, keen to get on with the writing and bring our chocolate room to life.

‘Right.’ I close my eyes. ‘I’m imagining a wall of chocolate, floor-to-ceiling, and I snap off a square and it’s like a fizzy explosion in my mouth.’ I open my eyes.

Olivia is staring at me, mouth slightly open.

‘Was that any good?’ I ask.

‘No,’ she says.

I try another approach. ‘Imagine a room of pick ‘n’ mix — like the one at the cinema.’

‘The one where you said the sweets cost more than your mortgage?’ Olivia says.

‘Yes.’

She’d been four. And it felt perfectly sensible to let her help herself to any sweets she wanted. She’d been so excited, scooping out the cola bottles and strawberry jellies, using what was basically a shovel. ‘Another of these, another of those and another and another,’ she said as she shovelled.

She’d looked so happy and adorable. We stood in the doorway, the doting auntie and uncle, watching the simple joy of a child in a sweet shop. After a few minutes, I realised she wasn’t going to stop.

‘Let’s weigh them and pay,’ I said.

‘Just one more…’ And she’d quickly done another lap, lifting more sweets into the bag, which she now needed two hands to carry. She heaved it onto the scales and the price flashed up on the screen.

‘How much?’ I stood in the queue and almost wept, looking around to see if anyone was watching so we could discreetly put some back.

‘We can’t put them back,’ Chris said, reading my mind.

So we paid. And just as I was getting over the shock, I realised that all that sugar in such a small person was not a good idea. ‘Eat them after the film,’ I’d suggested. ‘Save them for when you’re with your mummy.’ And she had. My sister’s still not forgiven me.

Chris looks up from his desk. ‘Auntie Liz and I are still having nightmares about how expensive the pick ‘n’ mix was.’

Olivia laughs. ‘Auntie Liz’s face when she realised how much.’

‘Can we focus on the writing, please,’ I say in my teacher voice.

‘Are you pretending you’re a teacher again?’ Olivia asks.

‘Yes.’ My life as a teacher seems a long time ago, but I try to remember the basics. ‘Before we start, we need words and lots of them. Describing words.’

‘Adjectives,’ Olivia says. ‘That’s what Miss wants.’ She picks up her pen, looks down at her paper.

‘How would you feel standing in a chocolate room?’ I ask.

Olivia is busy scribbling down her ideas. I look at Chris and smile. ‘What would I be like?’

‘Fat,’ he says.

I ignore him. ‘Imagine a wall of chocolate.’

‘That bar your mum got you for Christmas was almost as big,’ he says.

‘Big!’ Olivia shouts. ‘Miss says big is the most disgusting describing word in the world.’

‘It is. What can you say instead?’ I ask.

‘Huge, enormous, gigantic.’

I nod and smile, imagining enormous blocks of chocolate.

‘You really want to go to the chocolate factory, don’t you?’ Olivia says.

‘I certainly do!’

As Olivia is crafting her first sentences, I wander around the chocolate room of my mind. I’m reaching out, about to take a square when my phone rings. It’s my mum.

‘I’ll get this and call you back,’ I tell Liv.

Before I’ve even said hello, Mum is already ranting.

‘Did you know Mary’s daughter has had the vaccine, and she’s only in her forties?

‘Has she?’ I have no idea who Mary is, never mind her daughter.

‘She’s jumping the queue. What about me and your dad? We’ve not heard a thing.’

‘They said mid-February for the over-seventies,’ I say.

‘So why are the young ones pushing in?’

‘Maybe she’s got an underlying health condition.’

‘Apparently, she’s got asthma.’ From her tone, it’s obvious that she thinks Mary’s daughter does not have asthma.

‘We’ll all get them eventually,’ I say, wanting to get back to my chocolate factory.

‘But you’ve got asthma. Why haven’t you been called up?’

‘I don’t know!’ Just listening to my mother, my blood pressure rockets. I really need to get back to the chocolate. ‘Can we talk later? I’m home-schooling. Olivia needs help with something.’

‘Why didn’t you say? I’ll leave you to it.’ She hangs up without saying bye.

I phone Liv. ‘Where were we?’

‘We’ve walked in. There’s the chocolate wall in front of us. Then on the ceiling cola bottle jellies are dangling like icicles.’

‘Oh, lovely. The icicles will get you points,’ I say.

‘Yes, Miss wants similes.’

Next, we have a chocolate fountain — with gushing chocolate — and there are red, yellow and green Jelly Babies, all dusted in sugar, and it smells of fruit and cinnamon. It’s a magical place to be.

‘I’m really pleased with that writing,’ Olivia says when we’ve finished. ‘I like the colours.’

‘It’s good.’ I’m pleased with it too. It’s been wonderful to write just for the fun of writing, and not because I need to bash out five hundred words on diarrhoea for the day job.

‘Maths next,’ Olivia says, holding up her maths book.

At the mention of maths, my heart beats erratically. ‘Not my thing, I’ll pass you to Chris.’

‘I’ve got my own maths to do!’ He points to his spreadsheet, then takes the phone.

Olivia reads a mathematical question. It’s a long one. The type in which someone called Peter is driving a bus and four people get on and two get off and then another four get on and you have to work out how many people are on the bus when it stops. I used to hate those questions at school. My mind would always start wondering where the bus was going, what they did when they got there, and whether they’d had a good day.

I can’t even be in the same room as the maths chat. ‘I’ll leave you with Uncle Chris. I have to get back to work.’

I take my laptop and head for the kitchen table. After making another cup of tea, I sit down to write, hoping that inspiration will strike. I tap the keyboard and begin typing. The words are not quite gushing like the chocolate fountain, but there is a steady trickle. It’s progress.

A few minutes more, and I’m bashing the keyboard in my usual ferocious way as my fingers struggle to keep pace with my thoughts. I can’t help but smile. An hour inside Charlie’s chocolate factory is just what I needed.

.

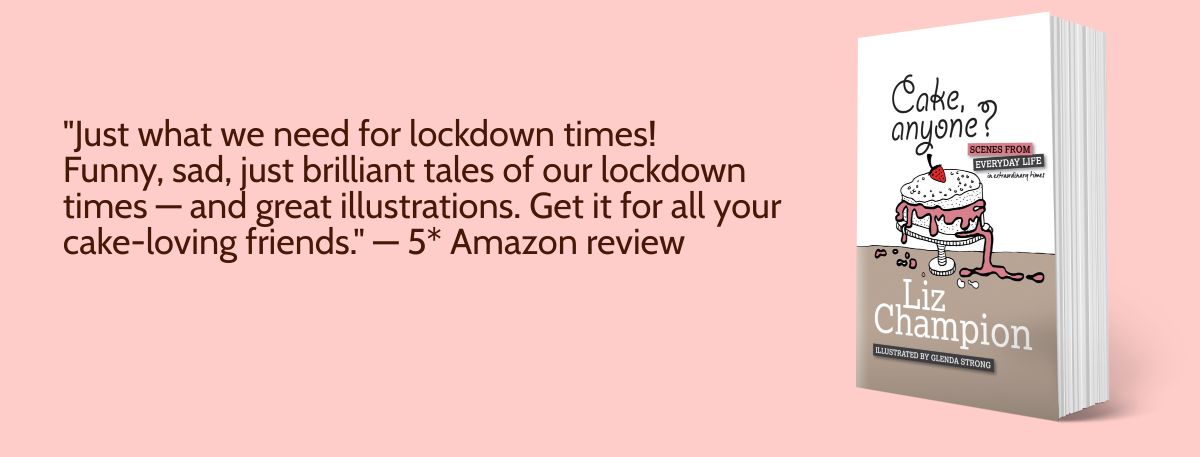

OUT NOW: CAKE, ANYONE? SCENES FROM EVERYDAY LIFE IN EXTRAORDINARY TIMES. Available for £4.99.

Liz, this is brilliant! One of the best things I’ve read in a long, long time. 🙂

Amelia, Thank you! So pleased you enjoyed it.